Walking Meditation: The Practice of Being Mindful of the Third Phenomenon

When you struggle with breath meditation, I want you to understand that walking meditation offers an equally profound path to insight. I practice walking meditation myself, and I want to share with you how this simple yet powerful method can transform your understanding of reality.

Finding Your Practice Ground

To begin walking meditation, you need to find a safe, relatively short, and quiet path. The length doesn’t need to be extensive—what matters is that you can walk slowly and mindfully without external disturbances. When you start walking, your task is beautifully simple: be mindful of the third phenomenon that arises when your foot touches the ground. Just maintain awareness of that contact sensation as you take each step.

I understand that some people find it difficult to sit for long periods, especially if they’re not accustomed to formal sitting meditation. The body becomes restless, the mind wanders, and the practice feels forced. In such cases, walking meditation can be remarkably effective because it works with the body’s natural movement rather than against it.

Understanding the Third Phenomenon

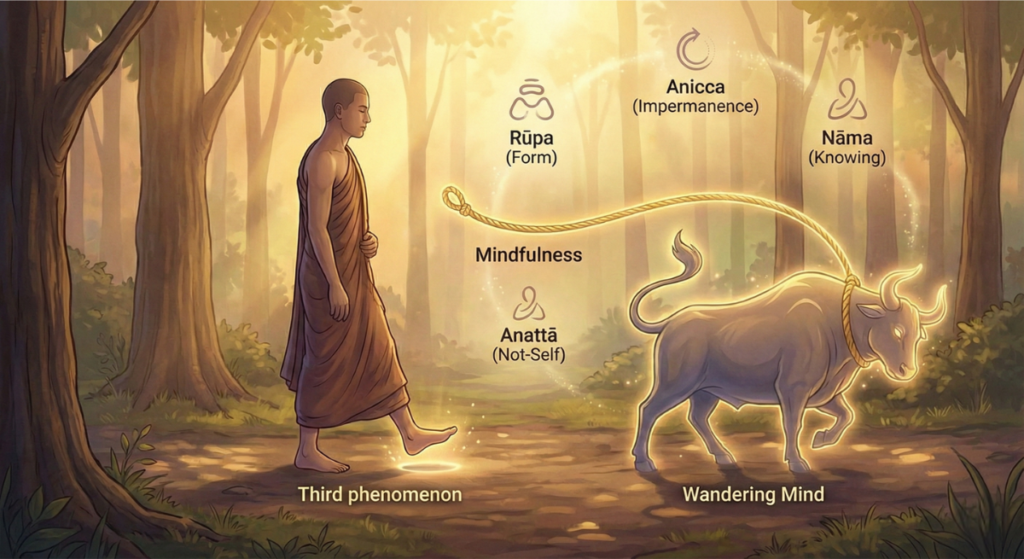

Let me explain what I mean by “ being mindful of the third phenomenon.” When your foot touches the floor during walking, something extraordinary happens if you pay close attention. Both the foot and the floor begin to disappear from your perception. What remains clearly discernible is only the distinct touch sensation itself—this is the third phenomenon. The foot is one thing, the floor is another, but the contact sensation that arises between them is the third element, and this is where your mindfulness should rest.

This practice reveals something profound about the nature of reality. You see, form never changes from old to new throughout life. Your legs and arms remain as legs and arms. But the elements like hardness, pressure, and movement—these arise and cease in various ways even within a single footstep. Forms belong to the realm of self-identity view (sakkāya-diṭṭhi). Elements belong to the realm of right view (sammā-diṭṭhi).

When you walk mindfully in this way, you begin to perceive only the qualities of touch—these rūpa and nāma of touch arising and passing, one after another. The object being sensed is rūpa; the knowing of it is nāma. This is how you come to understand ultimate reality directly, not through concepts but through immediate experience.

The Mechanics of Practice

As you practice walking meditation, you will notice that as soon as you start walking, the awareness of contact sensation becomes prominent. This happens naturally when your mindfulness is properly established. You don’t need to create anything artificial or force your attention unnaturally. Simply walk slowly and maintain a gentle, continuous awareness of the sensation of contact during each step.

What you’re actually observing is the arising of body-consciousness (kāya-viññāṇa) when foot touches floor—this is what I call the preceding mind. Being mindful of that is the subsequent mind. As the Venerable Mogok Sayadaw beautifully explained, when you practice in this way, defilements (kilesa) have no opportunity to infiltrate between these moments. Contact, knowing, and mindfulness follow in rapid succession, leaving no gap for craving, conceit, or wrong view to enter.

The preceding mind is arising and passing, while the following mind is the path (magga). This is simply the subsequent mind contemplating the preceding mind. When you lift your foot, there is volition (cetanā) that initiates the movement—this is the preceding mind. Noticing that volition arises and ceases is the subsequent mind. If you continue to be mindful and contemplate in this way, it will gradually become clear in your understanding.

The Deeper Transformation

I want you to understand something crucial: every footstep you take is driven by cetanā (volition) working behind the scenes. When you walk to the temple or on pilgrimage, you may think “ I am walking” or “ I am going to pay respects to the Buddha,” and you know this generates kamma-kusala (wholesome kamma). But when you become mindful of the cetanā itself—when you notice the volition arising and ceasing with each step—this awareness becomes ñāṇa-kusala (wisdom-wholesome).

The kamma-kusala from your intention to visit the temple can only take you as far as a pleasant rebirth. But the ñāṇa-kusala that arises from being mindful of the cetanā itself—this can lead you all the way to Nibbāna, the cessation of suffering. This is why I say: cultivate wholesome volition for good kamma, cultivate mindfulness for good wisdom. Good kamma brings comfort in living; good wisdom brings comfort in understanding.

The Path to Spontaneous Mindfulness

When you first begin this practice, you will need to place your mindfulness deliberately on the walking sensation. You might think to yourself, “ Now I will be mindful of the contact sensation with each step.” This is what we call “ Placed Mindfulness” —it requires intentional effort and conscious direction.

But as your practice deepens and your faculties of mindfulness, effort, and concentration become truly robust, something wonderful happens. Mindfulness arises naturally without requiring the deliberate effort that was once necessary. As soon as your foot touches the ground, the mindful mind that recognizes the contact automatically emerges and performs its task. You no longer need to force yourself by thinking “ I must be mindful.” Instead, mindfulness simply is present, spontaneously being aware of the object. This state is what we call “ Developed Mindfulness” (bhāvita-sati) or “ Spontaneous Mindfulness” (paṭilabdha-sati).

When you reach this stage, you will notice that mindfulness operates automatically even during everyday activities. When you wash your face, the cool sensations arise spontaneously in your awareness. When you eat, the taste sensations appear clearly without deliberate observation. When you walk, the contact sensations manifest immediately. At this stage, you might no longer feel that you are forcing yourself; instead, it seems as though you are passively observing your mindfulness working naturally from the sidelines. This clearly indicates that your mindfulness has reached a robust, self-sustaining state.

Walking Toward Liberation

Let me share with you what happens as this practice matures. We live our lives solely through the momentary interplay of mind-and-matter (rūpa-nāma). When touch occurs, our existence is defined by the mind-and-matter of that very touch. When your foot takes a step, you experience life in that moment of contact; the moment the contact ceases, that mind-and-matter fades. With the next step, a new instance of mind-and-matter arises—and as the foot is lifted, that brief “ life” is lost once again.

When you come to understand that life is nothing more than these fleeting moments of mind-and-matter, your identification with the body diminishes. You begin to see that because each moment vanishes as soon as it appears, it is insubstantial (tuccha). In that very recognition, your craving, conceit, and wrong view (taṇhā-māna-diṭṭhi) dissolve. Without this insight, you tend to hold yourself in high esteem, thinking “ I am walking,” “ I am practicing,” “ I am progressing.” But when you fully grasp the nature of your own momentary mind-and-matter, you come to see that “ I” am nothing. In that realization, both attachment and pride fall away.

The Supreme Teaching

I want you to understand that the Lord Buddha’s main doctrine is anattā (not-self). The anattā doctrine points to cause and effect. In the entire world, there is no effect without a cause. This principle is absolute. When you practice walking meditation with clear mindfulness of the contact sensation, you are directly investigating this law of cause and effect. You see the volition arise as cause, the movement occur as effect. You see the foot touch the ground as cause, the sensation arise as effect. You see the sensation arise as cause, consciousness of it arise as effect.

The Buddha proclaimed: “ Ekāyano ayaṃ, bhikkhave, maggo…” – “ This, monks, is the one and only path…” What he meant is that the cultivation of mindfulness is the sole indispensable method for breaking free from the suffering of saṃsāra and for realizing Nibbāna. The mindfulness I am teaching you is not the ordinary mindfulness for crossing the street safely—that kind of awareness every human already possesses. The Blessed Buddha did not need to fulfill the pāramī (perfections) for four incalculable aeons and one hundred thousand world-cycles just to teach that basic level of awareness.

The mindfulness I am guiding you toward is mindfulness that can take ultimate reality (paramattha) as its object. This is mindfulness that sees beyond concepts and forms, that penetrates to the elements themselves, that recognizes the arising and passing of phenomena moment by moment. This is the mindfulness that leads to liberation.

Practical Guidance

So when you practice, walk slowly on your chosen path. Let your attention rest gently but firmly on the sensation of contact with each step. When the foot lifts, be aware. When it moves forward, be aware. When it descends and touches the ground, be especially aware of that contact sensation. Don’t think about the foot or the floor—let these concepts fade into the background. Rest your awareness in the direct experience of touch itself.

If your mind wanders—and it will, especially at first—simply return your attention to the contact sensation with the next step. Don’t be discouraged. The practice is not about perfect concentration from the beginning; it’s about continuous return to the object, about patient cultivation of mindfulness through repetition and gentle persistence.

With practice, you will notice that the awareness of contact sensation becomes prominent almost immediately when you begin walking. The mindfulness will grow stronger, more stable, more continuous. Eventually, it will become spontaneous, arising effortlessly with each step. And in that continuous awareness, you will begin to see the truth of impermanence (anicca), suffering (dukkha), and not-self (anattā) directly, not as concepts but as lived reality.

This is the path I walk. This is the path I teach. This is the path that leads to the end of suffering. Walk it with patience, with diligence, with clear understanding. May your kamma be wholesome, may your wisdom be profound.

Sādhu, Sādhu, Sādhu.

Dr. Soe Lwin (Mandalay)

Teaching & Quiz

The Practice of Being Mindful of the Third Phenomenon

Walking Meditation as a path to Insight

1 Finding Your Practice Ground

When sitting meditation feels forced due to restlessness or body pain, walking meditation offers a profound alternative. It works with the body’s natural movement.

To begin, find a safe, quiet path. The length need not be extensive. The goal is simple: be mindful of the third phenomenon that arises when your foot touches the ground. Maintain awareness of that contact sensation with each step.

2 Understanding the Third Phenomenon

What is the “ Third Phenomenon” ?

- The Foot is one thing (First element).

- The Floor is another (Second element).

- The Contact Sensation arising between them is the Third Phenomenon.

When you pay close attention, the foot and floor disappear from perception, leaving only the distinct touch sensation. This reveals a deep truth: Forms (legs, arms) belong to self-identity view (sakkāya-diṭṭhi), while Elements (hardness, pressure) belong to right view (sammā-diṭṭhi).

“ The object being sensed is rūpa; the knowing of it is nāma. This is how you come to understand ultimate reality directly.”

3 The Mechanics & Deeper Transformation

As you walk, observe the arising of body-consciousness.

Preceding Mind

The volition (cetanā) to lift the foot, or the arising of contact sensation.

Subsequent Mind

The mindfulness that knows and contemplates the preceding mind.

Kamma vs. Wisdom: Walking to a temple with good intention generates kamma-kusala (wholesome kamma), leading to pleasant rebirth. However, being mindful of the volition (cetanā) itself generates ñāṇa-kusala (wisdom-wholesome), which can lead to Nibbāna.

4 Placed vs. Spontaneous Mindfulness

Placed Mindfulness

Requires intentional effort. “ Now I will be mindful.” Common at the start of practice.

Spontaneous Mindfulness (Paṭilabdha-sati)

Mindfulness arises naturally without force. It operates automatically even during daily tasks like washing your face or eating.

5 The Supreme Teaching: Anattā

The Buddha’s main doctrine is anattā (not-self), which points to cause and effect.

By seeing that life is just fleeting moments of mind-and-matter (rūpa-nāma) arising and passing, your identification with the body diminishes. You realize “ I” am nothing.

“ Cultivate wholesome volition for good kamma, cultivate mindfulness for good wisdom.”

Quiz Complete!

You have completed the path of understanding.

Final Score