Understanding Ānāpānasati: The Foundation of Mindfulness Practice

When I teach meditation, I want you to understand that ānāpānasati—mindfulness of breathing—is not merely a simple breathing exercise, but rather a profound doorway into the entire path of liberation that the Buddha taught. Let me explain this carefully, because many people misunderstand what we are actually doing when we observe the breath.

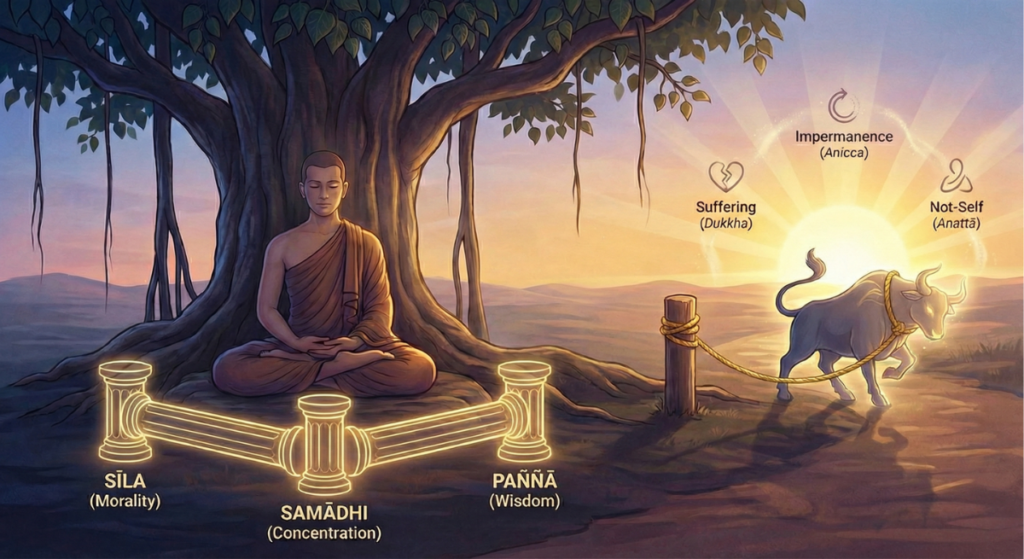

The Place of Ānāpānasati Within the Three Trainings

You must first understand where this practice fits within the Buddha’s complete teaching. The Buddha’s path is organized into three trainings (tisso sikkhā): sīla (morality), samādhi (concentration), and paññā (wisdom). These three are not separate compartments but are mutually supportive and interdependent. When sīla is well-established, samādhi can be more easily developed. When samādhi is strong and stable, paññā (wisdom) becomes clear and penetrating. And when paññā arises, you gain deeper understanding, appreciation, and commitment to maintaining sīla. Progress unfolds through this reciprocal reinforcement.

At this stage in your meditation practice—whether you are in a retreat or maintaining daily dedicated practice—what you are primarily cultivating are sati (mindfulness), viriya (effort), and samādhi (concentration), all of which belong to the Training in Concentration (samādhi sikkha). Why do I emphasize this? Because these form the essential foundation for the arising of paññā (wisdom). When your mind is scattered, or overwhelmed by the five hindrances (nīvaraṇa), you cannot rightly discern mental and physical phenomena. That is why you must first strengthen mindfulness, effort, and concentration to calm the mind. Only when these qualities are well-developed can wisdom genuinely arise.

What We Are Actually Doing: Establishing Mindfulness and Effort

Now, when I teach you to observe the in-and-out breath, what exactly are we doing? Let me be very clear: practicing meditation is fundamentally just doing two things with perseverance. First, mindfulness (sati)—staying conscious of the object, being aware. Second, effort (viriya)—striving, guarding, and maintaining so that mindfulness does not slip away from the object and the mind does not wander.

You must focus primarily on these two—mindfulness and effort. Do not have any expectations at all about how you will see the arising and passing away of phenomena, how you will encounter mind and matter, or how you must overcome painful feelings (vedanā). Those are the resultant effects that will naturally arise when mindfulness, effort, and concentration become strong. For now, you must focus on building up the causal factors—mindfulness and effort—to make them firm and strong.

Let me give you an example to make this clearer. Think of the in-and-out breath as a post. Mindfulness is like the rope tied to that post. Your mind is like a wild bull tied with that rope. Effort is the strength that pulls the rope taut. Even though your mind, like a wild bull, wants to run here and there, only when you can pull the rope (mindfulness) taut to the post (object) with the strength of effort will the mind become calm. If you let the rope go slack or if the strength pulling it (effort) is weak, your mind will wander off. Therefore, it is necessary to always keep the rope of mindfulness pulled taut with effort.

How Concentration Actually Arises

Many people wonder, “ How do I develop concentration?” I want you to understand that concentration is not something you have to create separately—it is simply the natural result of strong mindfulness and effort working together. Let me explain the process step by step so you can see the causal relationship clearly.

First, mindfulness (sati) notes a meditation object, such as the in-and-out breath. Second, effort (viriya) supports and maintains that mindfulness from behind, ensuring it does not slip away from the object and remains steady. Third, when mindfulness and effort become strong in this way, and due to the support of effort, mindfulness is able to rest on the object continuously and steadily—that stability is called concentration (samādhi).

Therefore, you must understand this crucial point: a wandering mind wanders not because there is no concentration, but because effort is weak. Because effort fails to support mindfulness from behind, mindfulness cannot stay continuously on the object. This is why I emphasize that your main task now is “ establishing mindfulness with effort.” When you understand this causal process with wisdom, you will know exactly what to do in your practice.

Working With the Wandering Mind

The first of the three main obstacles you will face when meditating is a wandering mind. When you first start practicing, your mindfulness is not very strong. Therefore, after being aware for a short while, it tends to slip off the object. Your mind tends to wander here and there. Why does this happen? It is because of weak effort (viriya). The mind wanders not because there is no concentration, but because there is no effort.

Now, what should you do when your mind wanders? Do not worry or find fault with the wandering mind. This is very important. Instead, follow this method: First, immediately know that the mind has wandered. Recognizing “ Oh, my mind has wandered” is mindfulness (sati). Second, immediately pull it back to the primary object (the in-and-out breath) with effort. Do not follow the thought and continue thinking about it. Do not analyze why the mind wandered. Immediately return to your in-and-out breath with effort. This is effort (viriya).

You must understand something profound here: when you notice that your mind has wandered and you bring it back, you are replacing the unwholesome with the wholesome. The essence of vipassanā meditation is this very process of replacing and eradicating the unwholesome with the wholesome. This is also the summary of the Buddha’s entire teaching. Giving charity, observing precepts, developing tranquility (samatha), and practicing vipassanā are all methods of eradicating the unwholesome with the wholesome. You must strive with enthusiasm, knowing with wisdom that this work of noticing every time the mind wanders and bringing it back is a very important process of cultivating wholesomeness. Do not take this effort lightly as if it were nothing. It is said that when all unwholesome states are exhausted by conquering them with wholesome states, one becomes an Arahant.

Working With Sound and Physical Sensations

The second obstacle you will encounter is hearing sounds. While you are meditating, you will hear various sounds from the surroundings. Sound is an object of the ear. As the principle goes, “ when there is an object, a mind will arise,” so when there is a sound, a hearing-consciousness will arise; it is natural for the mind to go to the sound. Just as with a wandering mind, do not worry or find fault when your mind goes to a sound.

The method is the same as for a wandering mind. First, immediately know that the mind has gone to the sound. Recognizing “ Oh, I heard a sound” is mindfulness (sati). Second, immediately pull it back to the primary object (in-and-out breath). Do not follow the sound and listen to it. Do not follow it and think about its source. Immediately return to your primary object with effort. This is effort (viriya).

However, regarding sound, there is an additional point to be careful about. That is the tendency to develop an unpleasant mind (aversion/dosa) toward the sound. It is possible to become annoyed, thinking, “ The sounds are so loud, they are disturbing my meditation, don’t these people have any consideration?” This is a very common unwholesome mental reaction. You must be mindful not to let the mind reach that stage, not to let aversion arise. Hearing a sound is natural, but if you recognize it and bring the mind back, it becomes wholesome. You must try to stop at that level.

So, what if you hear sounds continuously? Let them be. Keep your mind on the primary object with firm, focused, and intense effort. This means to focus more on the in-and-out breath. Apply more effort. If your effort is strong, even though you hear sounds, your mind will remain stable on its object, and defilements (especially displeasure/domanassa) will not arise because of the sound. Even though you hear it, you will no longer be annoyed by it, and it will become a bare hearing experience.

The same principle applies to physical sensations like pain or numbness. First, immediately know that the mind has gone to the painful or numb spot. Recognizing the sensation “ It’s hurting” or “ It’s numb” is mindfulness (sati). Second, immediately pull the mind back to the primary object (in-and-out breath). Do not follow the pain and dwell on the feeling. Do not analyze it by thinking, “ How much does it hurt? What kind of pain is it?” Immediately return to your in-and-out breath with effort. This is effort (viriya).

At this point, a question may arise: “ Can’t I just note ‘pain, pain’ and observe its arising and passing away?” You can. However, that is more suitable for individuals whose mindfulness, effort, and concentration are strong and whose wisdom is more mature. For ordinary people, especially for meditators who have just entered a retreat, your mindfulness, effort, and concentration are not yet strong, so if you observe the pain directly, it is more likely that defilements will arise. How does your mind tend to react when there is pain? You might think, “ Oh, it hurts so much, I can’t bear it anymore, when will the time be up? I wish it would go away” —this is craving (lobha). Or you might think, “ Why do I have to sit through so much pain? I’m angry at the teacher who made me sit. I don’t like this pain, I’m frustrated” —this is dissatisfaction (dosa). Or you might think, “ Am I doing this right? Should I be observing the pain, or should I go back to the breath? What should I do?” —this is doubt (moha, vicikicchā).

These defilements can enter very easily. Great masters with mature pāramī (perfections) can see the arising and passing nature of the sensation just by noting “ pain, pain,” and can thereby abandon the defilements clinging to it. They can pull themselves out of the mud of defilements through their own strength. You are not like that yet.

Two Types of Effort: Physical and Mental

Now I want to explain something that many meditators do not clearly understand: there are actually two types of effort that you need to develop. The first is physical effort (kāyika-viriya). This means maintaining the physical posture with alertness and energy—sitting upright without slouching, keeping the body still and composed. When your body is alert and energized, your mind naturally becomes more alert as well.

The second type is mental effort (cetasika-viriya). This is the effort of the mind itself—gathering all your mental energy and focusing it entirely on that single point at the tip of the nose where the breath enters and exits. It is like jumping into the water with both feet—complete commitment. If you can focus your mind with this kind of mental effort, ordinary sounds and pains will not be able to come and disturb you.

Most of you don’t really know that you should establish this mental effort, nor do you know how to establish it. That is why when you meditate, if many sense objects arise or sensations become intense, your mind tends to wander off easily. Therefore, in addition to physical effort, you need to work on strengthening this mental effort as well.

The Type of Concentration We Are Developing

You must understand clearly what type of concentration we are developing in ānāpānasati practice. In the Buddha’s teaching, there are two main approaches to concentration. The first is jhāna concentration (appanā-samādhi), which is developed in samatha meditation by focusing on a single, unchanging conceptual object until the mind becomes deeply absorbed. The second is momentary concentration (khaṇika-samādhi), which is what we are developing in vipassanā practice.

In vipassanā, since the meditation objects are mind and matter phenomena, they are constantly arising and passing away—they are dynamic. For example, with the in-and-out breath, the sensations of touch, pressure, and pushing that arise at the tip of the nose arise briefly and then disappear. These sensations change moment by moment. Mindfulness and effort must be used to closely follow each of these changing points of experience, without letting the mind slip away.

Because the mind is concentrated on each individual moment, this type of concentration is called momentary concentration (khaṇika-samādhi). It is more closely linked with wisdom (paññā) and requires a stronger application of mindfulness (sati) and effort (viriya). This kind of concentration may not remain stable for as long a duration as jhāna concentration, but it works in close association with insight. Only when this momentary concentration becomes strong can you deeply penetrate and realize the true nature of the rapidly arising and passing mental and physical phenomena, through vipassanā wisdom (vipassanā-ñāṇa).

What we are currently teaching and practicing falls under the Vipassanā Vehicle (vipassanāyānika). Therefore, your main aim is to establish momentary concentration. If you observe the in-and-out breath in a flowing, generalized way—such as by noting “ in… out…” —or if you focus on conceptual objects like mental images (nimitta), you may drift into samatha concentration instead. In vipassanā, however, the task is to carefully catch and focus on the momentarily changing ultimate realities.

The Progression of Wisdom Through Ānāpānasati

Now I want to explain how wisdom develops through this practice, because it is not enough to simply observe; the deeper significance lies in understanding why you are observing and what the underlying process entails. Wisdom (ñāṇa) must accompany the practice. Often, you perform meditation superficially—just following instructions or relying on habitual knowledge—without deeply understanding the Dhamma principles involved. As a result, you may not progress as much as you could. Genuine growth depends on wise discernment of the step-by-step process and the causal relationships within the practice.

You must clearly see, with wisdom, how each stage of the practice connects to the next—how each moment conditions the one that follows. Let me explain this step by step: Why do you focus on the in-breath and out-breath? To establish mindfulness (sati). What supports and maintains that mindfulness? Effort (viriya). When mindfulness and effort become strong, what arises? Concentration (samādhi). When concentration is stable, what can you begin to discern? The true nature of mind and matter phenomena.

When you practice correctly, observing so that the preceding and subsequent minds connect, focusing on the “ third phenomenon” (the ultimate reality of the knowing consciousness and the touch sensation), then the ultimate mind and matter phenomena become clear in your wisdom. This is the stage called Knowledge of Analysing Mind and Matter (nāmarūpa-pariccheda-ñāṇa).

Next, you perceive, with wisdom, the causal relationship of mind and matter—for example, “ knowing arises because of touch.” This is the stage known as the Knowledge of Discerning Conditionality (paccaya-pariggaha-ñāṇa). Understanding the “ third phenomenon” that I have just discussed is very helpful for eradicating Wrong View with this kind of understanding. When you personally and practically understand that it is not “ I” touching or “ I” knowing, but that the touch and the knowing consciousness are arising on their own according to their nature as effects of converging causes and conditions, the attachment to “ I” can begin to fall away at the level of intellectual understanding. Only by building on this Right Understanding and continuing to meditate and develop it can you ascend to the actual stages of vipassanā insight.

From this point onward, you observe with wisdom the three characteristics: that mind-and-matter phenomena are impermanent (anicca), that because they are impermanent they are essentially suffering (dukkha), and that they are not subject to personal control—not-self (anattā). This relates to higher stages of insight-knowledge such as the Analytical Knowledge of Investigation (sammāsana-ñāṇa), the Knowledge of Arising and Passing Away (udayabbaya-ñāṇa), and the Knowledge of Dissolution (bhaṅga-ñāṇa).

As you repeatedly observe this arising and passing (udayabbaya) and mature, your mind’s agitation, craving, and aversion toward all conditioned phenomena (saṅkhāra) diminish, and you attain the insight-knowledge stage called Equanimity toward Formations (saṅkhārupekkhā-ñāṇa), a perspective that regards these conditioned phenomena with equanimity and non-agitation. At this stage, whether the object of observation is pleasant or unpleasant, your mind no longer reacts with strong attachment or aversion but accepts it as it is, simply acknowledging, “ It is just its own nature.” This equanimity is not born of ignorance but is a stable calm arising from deep penetrating wisdom.

The Development of Spontaneous Mindfulness

When you first begin practicing, you need what I call “ Placed Mindfulness.” You have to intentionally anchor your attention to the object, thinking things like, “ Now… I will be mindful of the in-and-out breath,” or “ I will be mindful of the contraction and expansion of the abdomen.” This kind of effortful focusing can be referred to as the deliberate effort that was once necessary.

However, when the faculties of mindfulness, effort, and concentration become truly robust, mindfulness arises naturally without requiring the deliberate effort that was once necessary. In other words, as soon as an object—such as a touch, a sound, or a thought—appears, the mindful mind that recognizes it automatically emerges and performs its task. There is no longer a need to force yourself by thinking, “ I must be mindful.” Instead, mindfulness simply is present, spontaneously being aware of the object. This state may be referred to as “ Developed Mindfulness” (bhāvita-sati) or “ Spontaneous Mindfulness” (paṭilabdha-sati), and it represents an important stage of progress in the practice of foundational mindfulness.

When you reach the “ Developed Mindfulness” stage, you will notice that mindfulness operates automatically even during everyday activities. For instance, when washing your face, you used to only register the concepts of “ face” and “ water.” Now, when water touches your face, the cool sensations—and likewise, when you rub your face, the tactile sensations—arise spontaneously in your awareness without the need for deliberate observation. This spontaneous mindfulness also manifests when washing your hands, eating, or walking. At this stage, you might no longer feel that you are forcing yourself; instead, it seems as though the practice is flowing naturally.

The Profound Benefits That Arise

When mindfulness and concentration strengthen and, especially, when wisdom (paññā) that sees things as they truly are becomes robust, your ability to manage your mind becomes exceptionally strong. You will find that the difficulties you once faced have become much easier.

For example, in abandoning the unwholesome: Previously, when encountering an anger-provoking stimulus, your mind might have erupted in anger, causing you to suffer for an extended period. Similarly, upon seeing a desirable object, craving would arise, and you would find yourself chasing after it. Now that mindfulness, concentration, and wisdom are strong, as soon as an object that could lead to unwholesomeness appears (for example, someone’s unjust words or an enticing sight), mindfulness immediately recognizes it. Wisdom promptly reflects, “ Oh… this is an object that can lead to unwholesomeness. It is merely of the nature of anicca, dukkha, and anattā. It is not something to cling to.” With the power of this mindfulness and wisdom, those unwholesome states of mind either do not arise at all or, if they do, they do not last long and are quickly quelled and dissipate.

On the other hand, in developing the wholesome: Previously, you might have felt that meditating, cultivating loving-kindness, or giving charity was tiring, unpleasant, or difficult. Now that mindfulness, concentration, and wisdom are strong, when you direct your attention to wholesome objects (for example, cultivating loving-kindness or reflecting on the Dhamma), your mind becomes very stable, and wisdom is able to appreciate its fleeting nature. In that very moment, you come to realize that every inhalation, every exhalation, every touch, and every instance of mindfulness cultivates boundless merit.

Therefore, I want you to understand that ānāpānasati is not a simple technique but a complete path that integrates mindfulness, effort, concentration, and wisdom. Through this practice, you are not merely watching the breath—you are systematically training your mind to see reality as it truly is, to abandon unwholesome states, to cultivate wholesome states, and ultimately to realize the profound truth of anicca, dukkha, and anattā that leads to liberation. This is the essence of what I teach, and this is the path you must walk with diligence, wisdom, and patient effort.

Dr. Soe Lwin (Mandalay)